The State of Robotics: Emerging Trends & Commercial Frontiers, Part II

While Part I explored the technical breakthroughs reshaping robotics, an equally consequential transformation is unfolding across the industry’s commercial landscape. Top engineers are leaving seven-figure salaries to launch ambitious startups. Mega funding rounds exceeding $100M are becoming increasingly common. Meanwhile, China has designated humanoid robotics as a national priority, pouring billions into R&D and manufacturing.

The scale of investment and government backing suggests this may be more than another hype cycle –it’s a high-stakes race to capture value in what could become the foundational technology platform of the next generation –one where the winners may capture billions in value while reshaping the nature of work itself.

But beneath the venture capital headlines and government proclamations, several fundamental questions remain that will influence the industry’s trajectory:

Which companies are best positioned to win in robotics?

Is China poised to dominate the robotics hardware market?

Will humanoids become the standard, or remain one form among many?

Can software-first companies compete with vertically-integrated giants?

Is robotics the next $10 trillion industry?

When will we reach the tipping point?

Let’s explore each in turn.

1. Which Companies are Best Positioned to Win in Robotics?

The race to build robotic foundation models (RFMs) has triggered a significant talent migration. Elite engineers from companies like Google DeepMind, NASA Jet Propulsion Lab, NVIDIA, and Amazon Robotics are increasingly leaving to build their own startups, betting that RFMs will take a similar “winner-take-most” dynamic to LLMs.

These startups aren't just focused on building better algorithms. They're pursuing a more integrated approach: generating training data, developing models, and building deployment infrastructure as unified systems. The underlying thesis is that robotics requires tight feedback loops between real-world deployment and model improvement –and that these loops, once established, become increasingly difficult for competitors to replicate.

This ambitious vision has captured the attention of both investors and tech giants alike: startups like Physical Intelligence (Pi), Field AI, and Skild AI have each announced $100M+ rounds, all within months of their initial fundraises. These startups believe they can move faster without legacy constraints, recruit top talent focused on ambitious visions, and take risks that large organizations won't. They're betting that robotics requires the kind of rapid iteration and technical risk-taking that favors smaller, more agile teams.

At the same time, incumbents aren’t standing idle. Major tech players are mobilizing significant resources:

Tesla projects a $10T long-term revenue opportunity for its Optimus robots, with plans to deploy “thousands” of units in Tesla factories by the end of 2025 (although it reportedly has only produced hundreds so far).

Meta recently announced a robotics division within Reality Labs focused on humanoid robots, with longer-term ambitions to develop the underlying AI, sensors, and software for third-party robots. The company also released V-JEPA2, a world model with robotic applications.

OpenAI is rebuilding its robotics team after shuttering it in 2020, and has invested in a number of robotics startups including Figure, 1X, and Pi.

NVIDIA is positioning itself as a key platform player, providing both hardware and software tools for emerging robotics startups.

Amazon absorbed Covariant’s leadership team and technology in 2024, integrating its AI into its vast fleet of robots. The company recently deployed its one millionth robot and launched DeepFleet, an RFM for coordinating fleet movement.

Apple is quietly working on both humanoid and non-humanoid projects, recently transitioning its robotics group from the AI division to the hardware engineering group. Apple is also exploring new human-robot training via the VisionPro.

As with LLMs, tech giants won’t yield ground easily when billions of dollars in potential value are at stake. OpenAI’s early lead with ChatGPT triggered an arms race, pulling in nearly every major tech company. We’re now seeing similar dynamics starting to play out in robotics. The same strategic moats –massive compute, proprietary data, and rapid feedback loops –are likely to be just as critical. Only the most well-capitalized players, whether startups or incumbents, will be able to shoulder the demands of building and maintaining leading systems.

Today’s wave of open-source Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models and accessible tooling has lowered the barrier to entry, sparking broad experimentation. But as the field matures, robotics may follow the arc of smartphones and other technologies: an initial period of fragmentation, followed by consolidation around a few dominant platforms as scale advantages compound. The next 18-24 months will reveal which approaches can move beyond demos to deployment, and whether today's well-funded startups can build moats before Big Tech fully mobilizes.

2. Is China Poised to Dominate the Robotics Hardware Market?

While U.S. companies currently lead in AI and foundation models, China is rapidly building its position as the global manufacturing hub for robotics. In a February 2025 analyst call, Tesla CEO Elon Musk made a striking prediction: while calling Optimus potentially “the biggest product of all time,” he also warned that Chinese manufacturers would likely produce nine of the ten best-selling robots globally.

Whether this proves accurate remains to be seen, but Musk's comments echo a familiar pattern –China's rise to dominance in manufacturing sectors from steel to smartphones to electric vehicles.

The data lends some credibility to this prediction. A 2025 Morgan Stanley report found that Chinese robotics startups are producing humanoids at roughly one-third the cost of their Western counterparts. As robotics moves from prototypes to mass production, this cost efficiency could become a decisive advantage. And it’s not just a function of labor costs –China’s edge stems from a powerful trifecta:

Manufacturing Scale: China’s decades of scaling complex technologies –from solar panels to EVs –have created unparalleled manufacturing capabilities. The country already leads in global industrial automation, with >3x more factory-installed robots than North America. This same expertise is now being applied to robotics, with firms like UBTech rapidly scaling humanoid production, sourcing more than 90% of components domestically and targeting deployments of up to 1,000 robots working in factories by 2025.

Supply Chain Ecosystem: Underpinning China’s manufacturing strength is an expansive, cost-efficient component supply chain. From 6-axis torque sensors to harmonic drives and planetary roller screws, China offers the widest array of humanoid components, often at a fraction of Western prices. Local suppliers are also innovating on quality and performance. For example, Inovance has developed a liquid cooled stator that improves motor performance for high-torque applications. As R&D investments mature and localization deepens, analysts expect further price declines, reinforcing China’s structural lead.

Government Backing: China’s central and municipal governments have thrown their weight behind robotics. In 2024, Beijing designated humanoids as a national priority, committing $20B+ to R&D, subsidies, and talent pipelines. This initiative has cascaded to local governments, with major cities like Beijing, Shandong, and Shenzhen incorporating humanoid robotics into their economic plans and providing grants to local companies.

So why isn’t the US all-in?

Despite world-class research in robotics, the US hasn’t matched China’s urgency in scaling up robotics infrastructure. Dr. Robert Ambrose, an industry veteran with decades of pioneering work in robotics and AI, sums up the existing hurdles succinctly:

Labor Politics: Anxiety over robots displacing American factory jobs despite manufacturing worker shortages and declining interest from younger generations

Talent Shortages: A limited pipeline of workers trained to build, operate, and maintain robotic systems

Capital Intensity: High technical and financial barriers that deter broader investment, outside of a few well-funded players

Policy Gaps: There is still no coherent national strategy for robotics, unlike China’s top-down industrial planning

The global competitive landscape in robotics appears to be taking shape along familiar lines. China is building advantages in cost-effective hardware production, while the U.S. currently leads in software, autonomy, and AI capabilities. This division mirrors patterns in other tech sectors, though robotics may carry higher strategic importance given that robots represent general-purpose labor platforms rather than single-function tools. And critically, they might someday build themselves.

This dynamic is influencing strategy at companies like Tesla, Figure, and Apptronik, which are pursuing tight integration between R&D and manufacturing to accelerate iteration cycles and leverage automation advantages. The approach aims to compete on innovation speed rather than pure cost. Meanwhile, Chinese firms continue to scale production capabilities and drive down costs –creating a race between different competitive strategies.

In the long run, the winner may not be the company that builds the most robots, but whoever achieves fully automated robot manufacturing: robots building robots at scale.

3. Will Humanoids Become the Standard, or Remain One Form Among Many?

The recent surge in humanoid investment has captivated the robotics world. In early 2025, Figure AI entered talks to raise $1.5B at a $39.5B valuation, just months after closing a $675M round. This staggering valuation, coupled with major raises by 1X ($100M), Apptronik ($350M), and Agility Robotics ($400M), signals a major bet: that humanoid robots will become the default platform for physical automation, just as smartphones became the universal interface for mobile computing.

At first glance, this “humanoid hypothesis” makes intuitive sense: our world is designed for humans, from door handles to elevators to workstations. A robot that fits in this world should, in theory, require fewer changes to existing infrastructure, and be capable of a broad range of tasks.

The thesis rests on three assumptions:

Universal Compatibility: Humanoids can work anywhere humans do

Maximum Versatility: General-purpose utility outweighs specialized machines

Economic Inevitability: Mass production will make humanoids cost-competitive over time

But reality may prove more fragmented than current valuations imply. Today’s humanoids are expensive (>$100K), mechanically complex, and difficult to manufacture at scale. Their reliability, maintenance demands, and energy efficiency still fall short of what's needed for mass deployment. These challenges suggest that humanoids may remain a premium or specialized solution –not the default.

At the same time, a growing ecosystem of non-humanoid robots is already delivering value across industries: wheeled systems dominate in warehouses and factories, where floors are flat and navigation is predictable; drones are increasingly making headway in delivery; quadrupeds are finding traction in areas like public safety and inspection; and bimanual manipulators (whether on static or mobile basis) are proving increasingly capable of performing a number of dexterous tasks. All of this points to a more diverse and specialized future –one where form follows function.

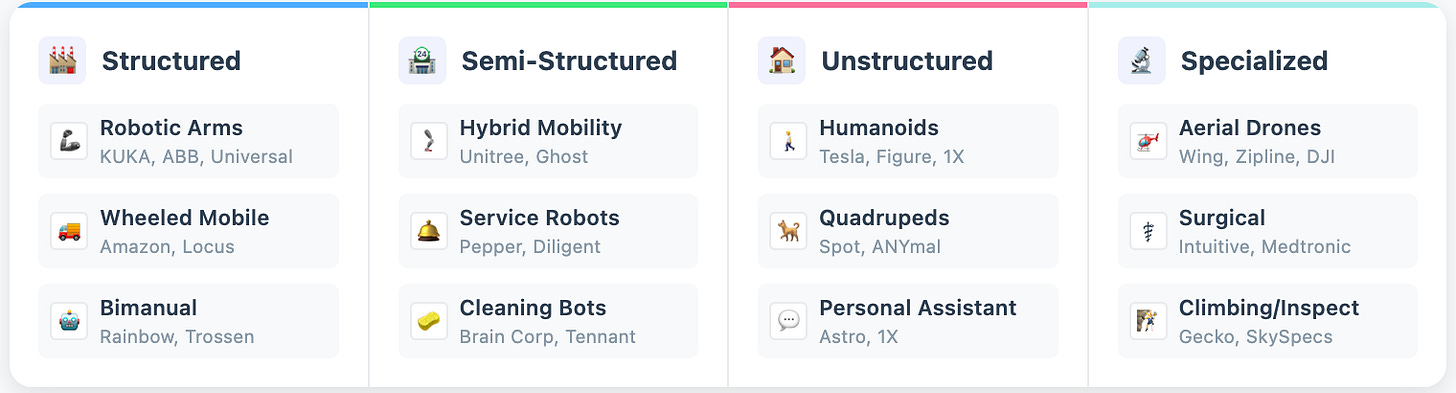

A Cambrian explosion in robot morphology

Rather than converging on a single dominant platform, robotics may be entering a “Cambrian explosion” –a rapid proliferation of different form factors, each created to thrive in distinct niches:

Structured environments (warehouses, factories): Robotic arms and bimanual manipulation platforms, whether wheeled or stationary, continue to dominate, optimized for efficiency and reliability

Semi-structured spaces (retail, hospitals): Wheeled or legged platforms, depending on navigation requirements

Unstructured spaces (homes, offices): Humanoid and human-inspired robots may find their footing, where compatibility and flexibility matter most

Specialized applications: Domain-specific designs –drones, surgical arms, climbing bots –optimized for unique tasks

Rather than a winner-take-all race, expect parallel evolution. The robotics leaders of the next decade will be those that deeply understand their deployment contexts, and choose the right morphology for the job. Humanoids may play an important role in the long-term, but they likely won’t monopolize it.

4. Can Software-First Startups Compete with Vertically-Integrated Giants?

As billions pour into robotics, companies face a critical strategic choice: should they vertically integrate across the entire stack or focus on core competencies, like software?

On one end of the spectrum, companies like Tesla and Figure are building complete robotic systems, including motors, actuators, and AI models. Their thesis is that tightly coupling hardware and software enables faster iteration, better performance, and long-term defensibility. By owning the full stack, these companies aim to optimize behavior holistically, from the user interface to low-level controls.

This approach has successful precedents: Apple's tight integration of hardware and software created the iPhone's seamless user experience, while Tesla's control over batteries, motors, and software enabled industry-leading performance in EVs. In robotics, vertical integrators argue they can achieve similar advantages –perfectly tuned actuators responding to AI models designed for bespoke hardware, with feedback loops that enable rapid improvement.

On the opposite end, companies like Field AI are building hardware-agnostic general-purpose robot “brains.” Their bet is that the real value lies in the intelligence layer, not the physical platform. By focusing solely on AI and controls, they can iterate faster on the hardest problems while leveraging existing hardware suppliers for components and manufacturing.

This model offers compelling advantages. Software companies can scale without massive capital requirements for manufacturing. They can serve multiple hardware platforms simultaneously, expanding their addressable market. And they can focus their best talent on the core challenge –making robots truly intelligent –rather than spreading resources across mechanical engineering, supply chain management, and manufacturing operations.

Each approach involves fundamental tradeoffs. Companies pursuing vertical integration gain maximum control over their systems and can optimize hardware and software together. However, they also face higher capital requirements, greater organizational complexity, and the risk that delays in one area –whether hardware or software development –can bottleneck their entire roadmap.

Software-focused companies can potentially scale faster with lower upfront investment and serve multiple hardware platforms simultaneously. But this flexibility comes at a cost: they depend on third-party hardware providers, have less control over the full user experience, and may struggle to access the rich operational data that comes from controlling deployments end-to-end.

However, the integration debate may obscure a more fundamental factor. The most important differentiator may not be integration strategy, but customer proximity. Robotics systems improve through real-world iteration –not in the lab, but in the field. The companies best positioned to win will be those closest to the deployment surface: those who control the user experience, access the richest operational data, and can close the feedback loop between learning and deployment.

5. Is Robotics the Next $10 Trillion Industry?

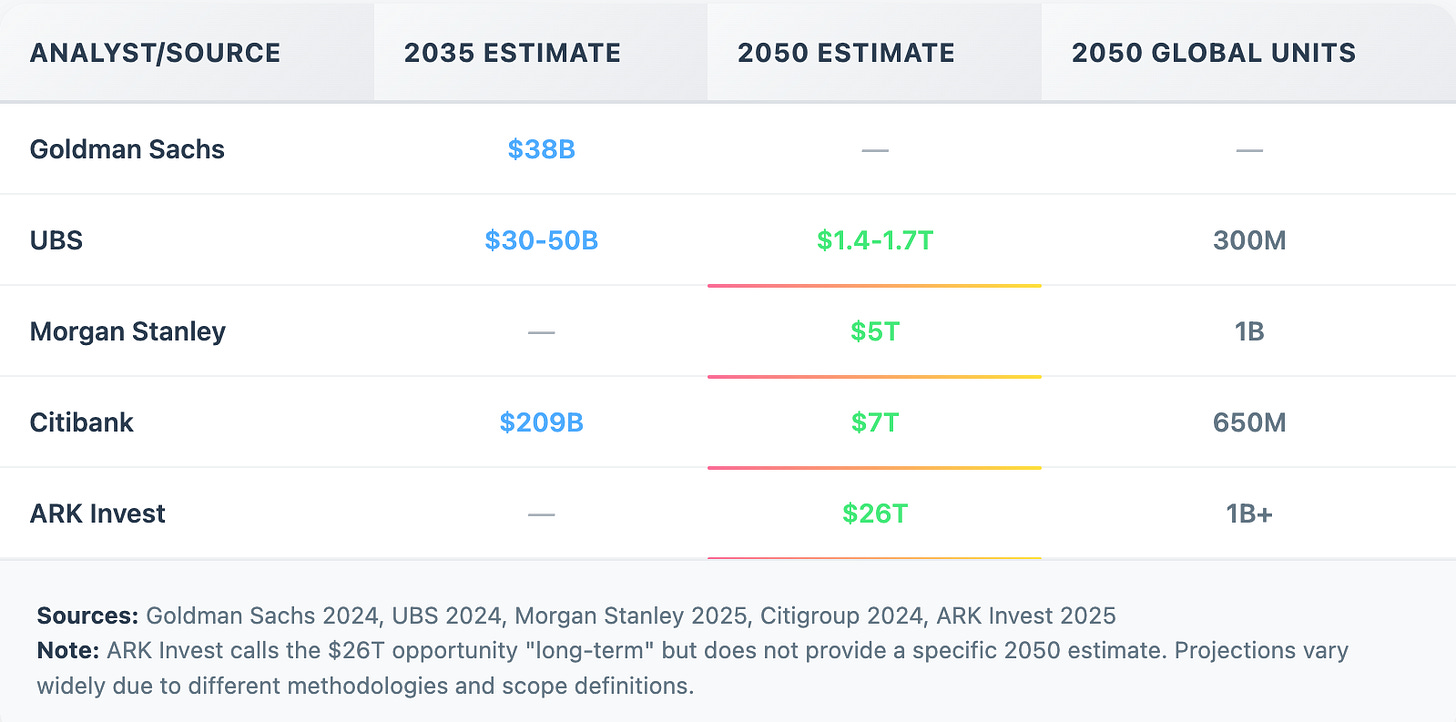

The robotics market isn’t just large –it is potentially transformative. As NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang said in early 2025, physical AI could become “the largest technology industry the world has ever seen.” While humanoid robots have captured recent investor and media attention, their real significance may be as a proxy for the broader potential of general-purpose robotics. The following market projections for humanoids thus represent not just one robot category, but a window into the total addressable market for intelligent automation:

While these projections vary widely in scope and timing, they reflect a growing consensus: robotics could become a foundational pillar of the 21st-century global economy –on par with vehicles, semiconductors, and cloud infrastructure. But this isn't just about replacing existing jobs –it's about creating entirely new categories of economic activity that become viable only at robot-scale economics.

What these projections do capture well is the size of the opportunity, and the forces driving it:

24/7 Labor at Low Cost: A $20,000 robot working around the clock equates to ~$1.14/hour after two years (excluding maintenance and energy costs); a fraction of the minimum wage in any developed market and competitive even with the lowest global labor costs.

Declining Hardware Costs: Goldman Sachs noted a 40% drop in humanoid manufacturing costs between 2022 and 2024, with current units now ranging from $30K to $150K. By 2050, mass-produced units could cost as little as $15K from Chinese suppliers.

New Economic Activity: As robot costs fall, entirely new service categories become viable for broad swaths of the population: 24/7 elder care, home security patrols, on-demand maintenance repairs, automated micro-farming, and countless applications we haven’t yet imagined.

Most analysts agree that commercial and industrial deployment will lead the charge, with Morgan Stanley projecting ~90% of humanoid units to be used in workplaces. But as costs decline toward Tesla’s long-term target of $20k/unit, the consumer market could explode and ultimately dwarf commercial use. Citi projects over 400M home-use humanoids by 2050, as falling prices and improved dexterity make in-home robots viable for cleaning, cooking, and caregiving.

The deeper question is whether robotics as a category can cross the chasm from prototypes to infrastructure. That will depend on more than capital –it will require reliability, seamless deployment, and societal trust. The $10 trillion question isn't whether robotics will transform the economy –it's how quickly. The companies that solve for reliability, deployment, and trust in the next decade will capture the lion's share of what may indeed become the largest technology market in history.

6. When Will We Reach the Tipping Point?

When will robots move beyond impressive demos to transform actual work? This question has defined the robotics industry for years, and the answer depends on solving challenges that extend far beyond better AI models. The autonomous vehicle industry offers a sobering parallel: despite Google's 2012 self-driving car announcement and tens of billions in investment, commercial deployment took more than a decade to emerge. Both industries face the same fundamental barriers: achieving reliability in unpredictable real-world conditions, proving economic viability at scale, and building the infrastructure required for mass adoption.

Robotics will follow its own path, but the tipping point will likely arrive when a few conditions converge:

Reliability at Scale: Robots must perform consistently in real-world conditions –handling unexpected obstacles, recovering from failures, and operating safely around humans for months without intervention. This demands more than better AI –it requires durable hardware, robust perception, intelligent fail-safes, and system-level resilience. Only then can robotics be trusted as infrastructure, not novelty.

Economics That Work: Robots must deliver value at scale. While $100K+ robots may work in high-value manufacturing, mass adoption requires sub-$50K price points for commercial use and sub-$20K for consumer markets –with total cost of ownership that beats human labor. This hinges on continued progress in hardware design, deployment tooling, and maintenance efficiency.

Deployment Infrastructure: Beyond technical and economic hurdles, the industry needs proven playbooks for deployment: standardized training protocols, predictable maintenance schedules, clear safety frameworks, and regulatory pathways that reduce adoption friction. Early adopters in manufacturing, logistics, and inspection will likely establish these patterns for others to follow.

The next 18 to 24 months will be critical. We’re likely to see which companies can move from demos to deployments, which business models actually generate profits, and which technical approaches scale beyond the lab.

As these ingredients come together, robotics will move from promising innovation to practical necessity –changing not just how we work, but who and what does the work in the global economy.

–

It’s an incredible moment to be working in robotics. If you're building in this area, please reach out to me at joanna@emersoncollective.com!